High in the Peruvian Andes, at an altitude where breathing becomes difficult and temperatures remain cold year-round, lies La Rinconada, widely recognized as the world’s highest permanent settlement. Built around small-scale gold mining, the city has grown rapidly over recent decades as people arrive in search of economic opportunity. Life at this elevation presents constant physical and environmental challenges, from limited infrastructure to harsh weather conditions, yet a strong sense of determination continues to shape daily routines. What makes La Rinconada especially significant is not only its extreme geography, but also what it reveals about global demand for natural resources and the human willingness to endure difficult conditions in pursuit of stability and income. This story explores how the city developed, how residents adapt to life at high altitude, and why La Rinconada has become an important example in discussions about labor, migration, and sustainable development. By looking beyond dramatic headlines, it offers a clearer understanding of a community living at the very edge of habitable environments.

Setting the Scene: Life at 5,100 Meters Above Sea Level

When I first learned about La Rinconada, I was struck by its description:

"La Rinconada, the closest inhabited place to the sky on Earth, where people are living above the clouds."

This city, perched at a staggering 5,100 meters (16,700 feet) in the Peruvian Andes, is not only the highest city in the world, but it is also a place where daily life is shaped by extreme altitude and the relentless pursuit of gold.

Higher Than Mont Blanc: The Geography of Extremes

To put La Rinconada’s elevation into perspective, it sits 300 meters higher than Mont Blanc, the tallest peak in Western Europe. Here, the air is so thin that oxygen levels are only about 50% of what you would find at sea level. Every breath feels different, and simple tasks can leave you breathless. The city is literally above the clouds, with the sky feeling closer than anywhere else on Earth.

Surviving in a Barren, Treeless Landscape

The environment of La Rinconada is unforgiving. Due to the low air pressure and harsh conditions, not a single tree can survive here. The land is barren, rocky, and exposed. There is no greenery to soften the landscape—just piles of mining debris, garbage, and the metal shacks that many residents call home. The lack of natural flora is a constant reminder of how inhospitable this place is for most forms of life.

Adapting to Thin Air: Human Physiology at Extreme Altitude

Living at such extreme altitude poses unique challenges for the human body. The reduced oxygen levels force residents to adapt in remarkable ways. Over generations, the people of La Rinconada have developed the ability to produce nearly twice as many red blood cells as those living at lower elevations. This adaptation helps their bodies carry more oxygen, making it possible to survive and work in an environment where most visitors would quickly become ill from altitude sickness.

Life Without Comforts: Primitive Living Conditions

Despite its location in the Peruvian Andes, La Rinconada is not a picturesque mountain town. Around 50,000 people live here, many drawn by the hope of striking it rich during the gold rush that surged between 2001 and 2012. Most homes are simple metal shacks, often lacking heating, electricity, or running water. At night, temperatures can drop below -10°C (14°F), making survival a daily struggle. The lack of infrastructure is evident everywhere—there are no proper sanitation systems, and public utilities are almost non-existent.

Altitude: 5,100 meters (16,700 feet)

Oxygen level: 50% of sea level

Resident population: Approximately 50,000

Nighttime temperature: Below -10°C (14°F)

Blood cell production: 2x normal compared to lowlanders

A City Shaped by Gold and Survival

The population of La Rinconada swelled as the demand for gold increased, despite the harsh living conditions. People arrived from across Peru and beyond, willing to endure the cold, the lack of oxygen, and the absence of basic comforts for a chance at a better life. The city’s existence is a testament to human resilience and the powerful draw of opportunity, even in the most challenging environments on Earth.

Human Body Adapts: Coping with Low Oxygen and Altitude Sickness

Living in La Rinconada, perched over 5,000 meters above sea level, means facing a world where oxygen levels are dramatically lower than what most people experience. For those of us used to life at sea level, climbing even above 2,000 meters in a single day can trigger altitude sickness. Here, the air is so thin that the body must work overtime just to function, and adaptation is not just a matter of comfort—it’s a matter of survival.

Altitude Sickness: The First Challenge

When someone ascends rapidly from sea level to high altitude, symptoms of altitude sickness often appear. These include headache, dizziness, nausea, coughing, and shortness of breath. In severe cases, fluid can accumulate in the lungs, making immediate medical help crucial. The body also loses about twice as much water through breathing at high altitude, so staying hydrated is essential. Before starting our journey, we made sure to pack plenty of food and clean drinking water, knowing how quickly dehydration can set in.

Oxygen Levels: Living with Less

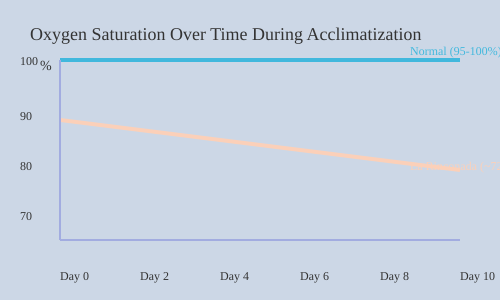

The atmosphere at this elevation is much thinner, making it harder to inhale enough oxygen. While the normal oxygen saturation in blood should be between 95 and 100%, residents of La Rinconada often have levels around 72%. As one local put it:

"The normal oxygen level in blood should be between 95 and 100%, below 80% vital organs become negatively affected."

Despite these low levels, people born and raised here have adapted to survive. However, this adaptation comes with significant health trade-offs.

Red Blood Cells: The Body’s Response

To compensate for the lack of oxygen, the body produces more red blood cells. In La Rinconada, the red blood cell count can be twice as high as at sea level. This helps carry more oxygen to vital organs, but it also makes the blood thicker, increasing the risk of blood vessel blockages and heart strain. Heart rates of 120 beats per minute or higher are common, even at rest. This constant stress on the heart and blood vessels pushes the limits of human endurance.

Chronic Mountain Sickness: The Cost of Adaptation

While many residents are well-adapted, long-term exposure to extreme altitude can lead to chronic mountain sickness (CMS). Symptoms include severe headaches, fatigue, and blue-tinged skin due to low oxygen. CMS can be fatal if not managed. Studies like Expedition 5300 are working to better understand these adaptations and the risks involved.

Traditional Remedies: Coca Leaves and Community Wisdom

Locals have developed traditional ways to cope with altitude sickness. Chewing coca leaves is a common practice here, believed to help reduce symptoms like headache and nausea. While coca leaves are illegal in many countries, in La Rinconada they are a vital part of daily life and high altitude living. These traditional remedies, along with community knowledge, help people manage the harsh conditions.

Hydration and Survival

Because the body loses water so quickly through rapid breathing, drinking enough fluids is a constant concern. Dehydration can make altitude sickness worse and increase the risk of other health problems. Clean water is as valuable as gold in this environment.

The Harsh Reality of Gold Mining and the Cachorreo System

Gold mining is the heartbeat of La Rinconada. Despite the extreme altitude, freezing temperatures, and life-threatening risks, thousands of people have settled here, drawn by the hope of striking gold. The city’s population exploded sixfold between 2001 and 2012, fueled by soaring gold prices. But beneath the promise of fortune lies a much harsher reality, shaped by illegal mining, dangerous working conditions, and a unique but deeply flawed labor system known as cachorreo.

Devil’s Paradise: Lawlessness and Control

La Rinconada is often called the Devil’s Paradise. As one miner put it,

"La Rinconada is also called the Devil's Paradise because it's ruled by illegal mining companies."

These companies operate outside the law, controlling the mines with violence and intimidation. Signs posted near the tunnel entrances warn that trespassers will be shot. The threat is real—mine operators enforce their rules with extreme measures, and the absence of formal oversight has turned the town into a place where lawlessness and crime thrive.

The Cachorreo Mining System: Work Without Wages

Most mine workers in La Rinconada do not receive a regular salary. In fact,

"The concept of a regular salary doesn't exist in La Rinconada."

Instead, miners work under the cachorreo system, an outdated and illegal arrangement. Here’s how it works:

Miners work for the mining company without pay for 30 days.

On the 31st day—known as cachorreo day—they are allowed to mine for themselves and keep whatever gold they find.

This system creates extreme economic instability. Some miners may find enough gold on their cachorreo day to make the month worthwhile, but many end up with little or nothing, effectively working for free. Their income is determined by luck, not effort or skill.

Women and Children: Marginalized and Vulnerable

Local beliefs and superstitions further shape life in La Rinconada. According to tradition, women are forbidden from entering the mines. It is said that the mountain’s spirit, known as the Sleeping Beauty, becomes jealous and brings disasters if a woman touches its gold. As a result, women earn a living by sifting through waste rocks outside the mines, searching for tiny flecks of gold discarded by the men. This work is grueling and pays very little.

Children are also a common sight on the mountainside, their cheeks marked by frostbite as they help their families search for gold in the freezing cold. Both women and children are excluded from the already meager opportunities available to male miners, making their lives even more precarious.

Life-Threatening Working Conditions

The dangers of gold mining in La Rinconada are ever-present. The tunnels are filled with poisonous gases, and the risk of explosions, roof collapses, and gas poisoning is high. In fact, mining accidents and deaths occur about 25 times more often than in advanced countries. Despite these dangers, compensation for a miner’s death is minimal—around $600, a small sum for a life lost. There are no safety nets, no health insurance, and no regular salaries. The combination of illegal mining operations and the cachorreo system leaves workers exposed to constant risk, with little hope for justice or security.

Faith and Survival

Amid these harsh realities, miners turn to local traditions for comfort and protection. Near the mining sites, figures decorated with dried flowers, fruits, and bottles of alcohol represent mountain gods. Workers pray here for safety and success, hoping for a lucky cachorreo day and a safe return home. In La Rinconada, gold mining is not just a job—it is a daily gamble with fate, shaped by luck, superstition, and the relentless pursuit of survival in the world’s highest mining town.

Environment in Crisis: Pollution from Mining Waste and Its Toxic Legacy

Living in La Rinconada, I see firsthand the true cost of gold. The environmental pollution here is impossible to ignore. Every day, the process of gold extraction creates mountains of mining waste, leaving a toxic legacy that affects every part of life above the clouds.

Mercury Contamination and Gold Extraction

Gold mining in La Rinconada relies heavily on mercury and cyanide. These chemicals are used to separate gold from rock, but they do not stay contained. Instead, they seep into the soil and water, contaminating everything they touch. As one local put it,

"People living by the stream grow their crops and raise their animals with water contaminated by mercury and cyanide."

For every gram of gold produced, about 2 grams of mercury are released into the environment. This mercury contamination is not just a local problem; it travels downstream, threatening agriculture and water supplies far beyond the city.

Mining Waste: The Hidden Cost of Gold

The scale of mining waste here is staggering.

"Each ring containing 8 grams of gold generates approximately 20 tons of waste during production."

That means for a single gold ring, miners must move and discard tons of rock. These piles of waste are everywhere, creating a landscape of debris and garbage. There is no formal waste management service in La Rinconada, so trash and mining debris simply pile up, filling the air with a sickening odor that never goes away.

Acid Mine Lake: A Toxic Landmark

At the top of the mountain, the environmental impact of mining is visible in the form of an acid mine lake. This deep red pool was created when rocks high in iron sulfate were extracted along with gold. When these rocks come into contact with water and air, they oxidize, turning the water a striking but deadly red. The acid mine lake is a constant reminder of the chemical reactions unleashed by mining waste, and it poses a serious risk to anyone living nearby.

Water Pollution and Its Ripple Effects

Local streams carry toxic water from the mines down into the valleys. This water is used by residents to irrigate crops and water livestock, spreading contamination through the food chain. Heavy metals and chemicals from mining waste accumulate in the soil, making it harder for plants to grow and threatening the health of animals and people alike. The water pollution here is not just an environmental issue—it is a daily health crisis.

Living Amidst Waste: No Sewage, No Solutions

Life in La Rinconada means living among piles of garbage and mining debris. There is no sewage system, so wastewater flows openly through the streets and public areas. With no government support or formal waste management, pollution is left unchecked. The frozen ground, with temperatures dropping below -10°C at night, makes natural remediation through soil and vegetation nearly impossible. As a result, the toxic legacy of mining waste continues to grow, threatening the health and longevity of everyone who calls this place home.

Mercury contamination from gold extraction poisons soil and water.

Acid mine lake formed by oxidized iron sulfate rocks creates a deep red, toxic pool.

Mining waste piles up with no formal management, filling the air with foul odors.

Water pollution impacts crops, livestock, and human health throughout the region.

No sewage system means wastewater contaminates streets and public spaces.

Living Conditions: Survival Amidst Crime, Cold, and Scarcity

Life in La Rinconada, perched high in the Peruvian Andes, is a daily test of endurance. The living conditions here are shaped by a harsh climate, minimal infrastructure, and a constant threat of crime. With a population of around 50,000—mostly migrants drawn by the promise of gold—this mining town is a place where survival depends on adapting to extreme challenges.

Homes Without Comfort: Metal Shacks and Shared Facilities

Most residents live in makeshift metal shacks, hammered together from sheets of tin and scrap. These shelters offer little protection from the biting cold, especially at night when temperatures can drop to minus 10 degrees Celsius, even in summer. There is no central heating, and electricity is a luxury found only on a few main streets. The majority of homes remain dark after sunset, forcing families to rely on candles or battery-powered lamps.

Private kitchens and bathrooms are rare. Instead, people share a handful of public toilets and communal bathhouses, which are often overcrowded and poorly maintained. Water is scarce and not always clean, making hygiene an ongoing struggle.

Crime in the Mining Town: A Constant Threat

The lack of government services and infrastructure has created a fertile ground for crime in La Rinconada. As one local put it,

"Crimes, especially stabbings and theft, are quite common here."

With no banks in town, miners carry their cash and gold with them, making them easy targets for robbers. Stabbings, muggings, and thefts are part of daily life, and the sense of insecurity is ever-present.

During my visit, we were accompanied by two undercover police officers for safety. Their presence was a reminder of the risks faced by locals and visitors alike. The town has only one police station, and its “calabozo”—a small holding cell—serves as the only jail. There is no real prison or legal system to deter offenders, so many crimes go unpunished.

Lack of Infrastructure: Darkness, Scarcity, and Limited Services

The lack of infrastructure in La Rinconada is evident at every turn. Electricity is unreliable and limited to certain areas, leaving most of the town in darkness at night. Garbage piles up in the side streets, becoming more visible at sunrise. There is no hospital in the city—just a tiny clinic with two to four rooms. As one resident told me,

"There is no hospital in the city, just a tiny clinic."

Serious injuries or illnesses require a dangerous journey down the mountain to the nearest real medical facility.

Education is also limited. There are a few primary schools and some secondary education options, but no opportunities for higher learning. Children play outside in the freezing air, their cheeks red from the cold, but their futures are constrained by the lack of resources and opportunities.

Social Life and Daily Survival

Despite these hardships, daily routines continue. Social life revolves around small markets, local cafes, and street vendors selling food and basic goods. Many residents chew coca leaves—a traditional habit believed to help with altitude sickness and fatigue. The air is dry and thin, making even simple tasks like walking feel exhausting. My own body felt tired and sore, with chapped lips and a constant sore throat from the altitude and cold.

La Rinconada’s community is resilient, but the combination of crime, cold weather, and scarcity makes survival a daily struggle. The lack of infrastructure and public services leaves people vulnerable, yet they persist, driven by the hope of striking gold and building a better future.

The Human Spirit: Resilience, Risks, and Dreams in the ‘Highest City’

Living in La Rinconada, the world’s highest gold mining city, is a true test of the human spirit. Every day, I see how resilience in a mining town is not just a word—it’s a way of life. Many of us came from other parts of Peru, drawn by stories of gold and the hope for a better future. The journey is not easy, but the promise of economic survival in the Peruvian Andes keeps us going, even as we face risks that most people can hardly imagine.

Chasing Fortune: The Economic Gamble

Gold mining here is both a blessing and a curse. The income is unpredictable, but often higher than the national average. A typical mine worker might earn around 2,000 Peruvian Soles a month, though this can go up or down depending on luck and the market. I remember meeting Ramiro, a miner who once found a single piece of gold ore weighing 200 grams—a rare and life-changing discovery. Yet, for most of us, the rewards are much smaller and the work never gets easier.

Physical and Mental Challenges at 5,000 Meters

Working at nearly 5,000 meters above sea level is a challenge even for those born in the Andes. I grew up in Puno, which sits at 3,800 meters, but coming here was still a shock to my body. The first days brought digestive issues and constant headaches. Many miners rely on traditional herbal teas and remedies to fight altitude sickness. Over time, we adapt, but the risks never fully go away.

The physical toll is visible in our hands—scarred, swollen, and often injured from crushing rocks to separate gold from stone. As Ramiro explained, “Injuries, injuries, injuries.” Accidents are common, and sadly, death is not rare. The average lifespan in La Rinconada is just 35 years. But as one miner told me,

“They don’t mean strength in muscle size, primarily it’s more about mental strength, about resilience, about mastering and considering the altitude.”

Mental Resilience and Community Support

Surviving here is not just about physical strength. Mental toughness is even more important. The isolation, the cold, the uncertainty of each day—these can break even the strongest body. We lean on each other, sharing stories, advice, and sometimes just a cup of hot tea. Community rituals and local beliefs, like offerings to the mountain gods, help us feel protected and connected. When government support is limited, we depend on our own traditions and each other to get by.

Risks, Crime, and the Cost of Survival

Mining is dangerous, not just because of accidents, but also because of crime. Robbery is a real threat when miners collect gold. Many of us worry about our families’ safety and future. When asked if he would want his children to work in the mines, one miner answered simply:

“No, because it is very, very dangerous.”

Dreams and Sacrifices: The Next Generation

Education is a luxury here. Many children start working in the mines at a young age, especially if their families cannot afford to send them elsewhere. Still, some miners, like Ramiro, dream of more for their children. His three kids are in university—a rare achievement in La Rinconada. For most families, the hope is that mining will give their children a chance to escape the cycle of risk and hardship.

Behind the statistics and the harsh realities, the story of La Rinconada is one of human adaptation, hope, and the relentless pursuit of a better life, even above the clouds.

Evening in La Rinconada: A Glimpse into Nightlife and Community Safety

As the sun sets over La Rinconada, the world’s highest gold mining city, the streets take on a new character. The cold intensifies, but so does the pulse of the town. Nighttime in this mining town is a paradox: it is both a time of lively social gatherings and heightened danger. The risks of crime in a mining town like La Rinconada become most apparent after dark, yet the community’s resilience and adaptability are equally visible.

Walking through the narrow, uneven streets, I notice that the town does not quiet down at night. Instead, it transforms. Miners, exhausted from long shifts underground, spill out into the streets and small bars. Markets stay open late, selling food, drinks, and basic necessities. Informal gatherings pop up on street corners and in makeshift venues. Despite the harsh environment and the ever-present threat of crime, the nightlife in this mining town is surprisingly vibrant. It is a testament to the human need for connection and relaxation, even in the most challenging circumstances.

However, the dangers are real and ever-present. As one local put it,

"Crimes, especially stabbings and theft, are quite common here."

The lack of formal banking means that miners carry their earnings—often in cash or small pieces of gold—on their person. This makes them easy targets for robbers. The absence of banks is not just an inconvenience; it is a major factor driving the high rates of theft and violence. With no secure place to store their wealth, residents must always be on guard.

Law enforcement in La Rinconada is limited. There is no permanent police station or jail, and official police presence is minimal. During my visit, I was advised to team up with two undercover police officers for safety while filming. Their role was to blend in and keep a watchful eye on our surroundings. As one of them explained,

"We're teaming up with two police officers to keep us safe while we're filming."

These officers followed us everywhere, their presence a reminder of the risks that come with simply walking the streets at night.

The challenges of law enforcement in Peru’s illegal mining towns are complex. The underground nature of much of the mining activity makes oversight difficult. Without a strong formal security infrastructure, community safety relies heavily on vigilance and informal policing. Residents look out for one another, and word travels quickly if trouble is brewing. Occasional police patrols offer some deterrence, but most people know that, ultimately, they are responsible for their own safety.

Despite these dangers, the spirit of La Rinconada’s people shines through. The nightlife is not just about entertainment; it is about survival, solidarity, and finding moments of joy in a harsh environment. The bars and markets are more than places to spend money—they are spaces where stories are shared, alliances are formed, and the fabric of the community is woven a little tighter each night.

In conclusion, evenings in La Rinconada reveal the city’s dual nature: a place of opportunity and risk, camaraderie and caution. The lack of formal security measures and the prevalence of crime in this mining town make community safety a shared responsibility. Yet, despite these challenges, life continues above the clouds, with residents carving out moments of normalcy and connection amid the uncertainty. La Rinconada’s nightlife is a powerful reminder of the resilience and adaptability required to thrive in the world’s highest—and perhaps most challenging—gold mining city.